- Home

- Parris, Matthew;

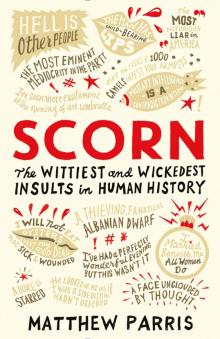

Scorn

Scorn Read online

SCORN

MATTHEW PARRIS worked for the Foreign Office before serving as an MP. He now writes as a columnist for The Times and the Spectator, and in 2011 won the Best Columnist award at the British Press Awards. He is the author of several books, including his autobiography Chance Witness and the bestselling The Spanish Ambassador’s Suitcase.

SCORN

The WITTIEST and WICKEDEST INSULTS in HUMAN HISTORY

MATTHEW PARRIS

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright © Matthew Parris, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 297 3

List of Contents

Introduction

HUMANITY

GOD AND RELIGION

MORALITY

NATIONS

PLACES

RACE

CLASS AND COURTESY

KINGS, QUEENS AND COMMONERS

PEOPLE, POLITICIANS AND GOVERNMENT

LEFT AND RIGHT

BRITISH POLITICS

PEERS

AUSTRALIAN POLITICS

AMERICAN POLITICS

POLITICS IN EUROPE AND BEYOND

WAR

EMPIRE

JOURNALISM

WRITERS, PUBLISHERS AND CRITICS

ART

MUSIC

THEATRE, FILM AND TELEVISION

DOCTORS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS

LAW AND LAWYERS

BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS

SPORT

CELEBRITY

FOOD AND DRINK

WOMEN AND MEN

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY

AGE

ANCIENTS, PRIMITIVES AND FOLK CURSES

EU REFERENDUM SCORN

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

This is a new anthology. The original Scorn, first published in 1994, prospered, was expanded, occasionally updated, and over the years appeared in a series of editions under different imprints, the last published eight years ago.

It was time for a clearout and re-stock. My assistant Robbie Smith and I decided to remove all the entries which seemed to us to have lost freshness or currency, and replace them with new material: some of it classic, some modern, some (given a British referendum and an election year in America) very recent indeed. This time we had the social media to plunder too; and two more prime ministers and half a dozen more party leaders as richly scorned as those that went before. And we wanted to beef up the entries on sport, a cornucopia of verbal abuse which I had hitherto neglected.

But the concept and basic format of the book remain the same. This is a whimsical and quirky collection, not a comprehensive dictionary. Nor is it a roll-call of literary merit. Silvio Berlusconi’s view of Angela Merkel – ‘an unfuckable lard-arse’ – is more lump-hammer than it is stiletto, and David Cameron’s alleged dalliance with a dead pig’s head drew a rich harvest of unprintables for us to print. But Noel Gallagher has given us more blade than bludgeon in his estimation of his brother Liam (‘a man with a fork in a world of soup’) and of Russell Brand (‘I couldn’t see him overthrowing a table of drinks’).

As before, we have not strung out the entries. Nor have we attempted to divide them into neat sections – ‘attacks on honour’, ‘attacks on appearance’, ‘attacks on ability’, etc. – or where would you put the remark that a man’s an incompetent, warty scoundrel? Instead we have tried to order these quotations in a way that allows them to speak, one to another.

Scanning our chosen remarks, many struck us as voices answering, echoing or rebuking each other down the ages. Often there seemed to be a dialogue going on, sometimes between people who had never heard of each other, sometimes between people who had. So we have tried to arrange our quotations as a sort of conversation, a ‘rally’. Often – not always – this works well. Sometimes the thread linking the dialogue is tenuous. Occasionally it may break. Rallies are not continuous. More than once a new voice will take the ball and run with it to a different court. But the feelings and ideas which link human expressions of scorn have enough in common to bounce these quotations off each other in a verbal sport which, at least sometimes, finds meaning and momentum.

The direction of the conversation has been signposted, by topic, very broadly in the heading at the beginning of each chapter. But we hope that this dialogue of voices has enough shape to invite its being read as a play, rather than consulted as a directory.

A play or directory of what? There are many excellent anthologies of insult, which we have consulted freely, some of which are credited in the Acknowledgements. But they leave so much out. ‘Insult’ is restrictive. ‘Scorn’ became our chosen title, for language can be used to express anger, hatred or disapprobation in a range of ways, of which simple insult is only a part. When Job curses the day he was conceived, he scorns life itself, but this is not really an insult. When Hobbes describes human society as ‘nasty, brutish, and short’, that is scorn, not insult. Neither is ‘witty’. Neither are ‘put-downs’. Wit and put-down – taking a verbal dig at others – are part of scorn, but not the whole of it. What we have tried to explore has been the dark side of language: humorous or serious, the use of the spoken and written word to hurt, wound or ridicule – to decry not just other persons but things too: and art, and life, and God himself.

The language of scorn, though vast, finds itself pursuing one or more of only four purposes. The first purpose is part factual, part polemical: the indictment – the conveying of hurtful facts or a hurtful argument. The literature is enormous and a little outside our theme; it finds a handful of examples in this book, such as Burke’s indictment of Warren Hastings and Geoffrey Howe’s of Margaret Thatcher.

The second is not to persuade or inform but to discomfort by a reference to existing, agreed knowledge: mockery – words which allude to something already known or suspected but whose mention, precisely because it is known, is hurtful. It could be, for example, a reference to someone’s big nose or humble parentage, or a physical or moral defect, a failing.

A third purpose of scorn comprises the very simplest form of abuse: the nose-thumb or snarl. This is the use of language in circumstances where the alternative might be to spit, an expression of pure hatred: ‘I loathe you’ or ‘ya-boo-sucks’. Such abuse conveys neither reason nor justification for the scorn; it conveys the scorn alone.

And finally the most curious of the four: the curse – a verbal formula used to invoke some malign external power to hurt one’s victim. This uses words as we might use a pin to stick in a voodoo doll.

It is fascinating to observe the decline in the potency and frequency of real cursing between ancient times and our own. God and the prophets do a great deal of it in the Old (and to some extent the New) Testament. Judaism and Islam use the curse. So did the ancient Egyptians – we include here a desecrator’s curse. In early times, in primitive cultures now, and very strongly in Eastern European cultures today, the use of language to curse is rich and lively, while the use of wit, indictment and other verbal abuse is often disappointingly crude.

As faith in the supernatural declines, so does the living curse. It

degenerates into a notional curse (‘damn you’, ‘a plague on both your houses’) which neither alludes to any actual failing nor conveys real information. It takes the form of a curse but is not a true curse: it is just a snarl. Modern cursing, though common, is uninteresting and routine because its soul is dead. We have lost our link with the supernatural. Correspondingly, other forms of scorn have been getting cleverer and wittier since the ancients. Words, stripped of the innate magical powers invoked by the simple act of pronouncing them, are obliged to carry interest and meaning in their own right.

As we gathered material for this book it became clear that the curse is really a subject on its own, and needs an anthology of its own; it cannot be properly integrated into other forms of verbal abuse. But it is too interesting to ignore. We have therefore included, along with ancient, primitive and folk abuse, a short section in which a sampler of curses, from ancient to modern times is assembled more as a list than as a dialogue.

Scorn has not been difficult to collect. The British Library, the Cambridge University Library, and appeals for suggestions to some 500 people in public or academic life have brought in a wealth of material. The problem, as ever, has been what to leave out. For a short book one must leave out most. This collection is therefore utterly and unapologetically idiosyncratic.

We have had a problem with Shakespeare. His work alone yields a treasury of insult, and such a collection has already been published. But, though he provides both wit and argument in his scorning, Shakespeare is really outstanding for his simple, schoolboyish, but verbally dazzling mockery. A glance at his vocabulary of insult gives the impression of relentless verbal heavy-shelling of a gloriously crude kind: ‘Thou drone, thou snail, thou slug, thou sot’, ‘breath of garliceaters!’, ‘these mad mustachio purple-hued maltworms!’, ‘leathern-jerkin, crystal-button, not-pated, agate-ring, puke-stocking, caddis-garter, smooth-tongue, Spanish pouch!’, ‘Whoreson, obscene, greasy tallow-catch’, ‘oh polished peturbation!’, ‘you Banbury cheese!’, ‘show your sheep-biting face’, ‘stale old mouse-eaten dry cheese’, ‘I will smite his noddles!’, ‘you whoreson upright rabbit!’, ‘you fustilarian! I’ll tickle your catastrophe!’ You could fill a book with this; we have decided to let others do so. Fascinating – to us – has been what, in Shakespeare’s case, the insults reveal about the insulter. Scorn tells us much – unwittingly – about the tastes and prejudices of the scorner. Shakespeare’s real horror was of grossness. Flick from the Shakespearean insults above to our insults from Britain’s 2016 EU referendum. Look on pp. 413–14 at the volley of tweets responding to Michael Gove. ‘Pork mannequin’, ‘incompetent ventriloquist-dummy-faced spunktrumpet’ … literally meaningless yet glorying in the sheer sound and image, this was a fusillade of which the Bard would have been proud.

Scorn also reveals much about the offensive-defensive divide. Its literature is crammed full – starting spectacularly with the Romans – of anti-homosexual invective, the key image being that of the effeminate, passive gay man who is buggered by others. Later, we begin to find confident answering scorn from the gay camp. There is much anti-Semitic insult, less insult returned. Anti-black invective is prodigious and rich; anti-white invective is edgy, defensive and scarce.

Eschewing political correctness, we’ve included much. Finally, attribution has often been a problem. A handful of individuals in political and literary history – Dr Johnson, Disraeli, Churchill, Dorothy Parker, for instance – have become so famous for their wit and scorn that the world has begun to attribute to them sayings which more careful research revealed were not theirs. The internet has only intensified this phenomenon, as Albert Einstein’s endlessly expanding list of witticisms and bon mots continues to demonstrate. Further, famous scorners begin to attract their Boswells, and find their conversation recorded and remembered, where ours would be forgotten, or unattributed. It seems that if you acquire a sufficiently powerful reputation for insult, the reputation will begin to grow by its own momentum, as everything you say is noted, and extra sayings of unknown authorship are attributed, speculatively, to you.

Gathering this collection has been fun. But many months of staring at unremitting lists of unpleasant remarks does, eventually, lower the spirits. We are looking forward to raising our eyes at last from the bucketful of misery and spite which follows.

Matthew Parris & Robbie Smith

Limehouse

Humanity

As I looked out into the night sky, across all those infinite stars, it made me realise how unimportant they are.

Peter Cook

Life starts out with everyone clapping when you take a poo and goes downhill from there.

Sloane Crosley

Life is a moderately good play with a badly written third act.

Truman Capote

Life itself is a universally fatal sexually transmitted disease.

Petr Skrabanek

You’re far from a perfect creature. But as far as natural selection is concerned, you’ll do, and that’s why you’re here.

Alice Roberts

Life doesn’t imitate art. It imitates bad television.

Woody Allen

Expecting the world to treat you fairly because you are a good person is like expecting the bull not to attack you because you are a vegetarian.

Dennis Wholey

So hard to teach but so easy to deceive.

Greek Stoic philosopher on mankind

It is not enough to succeed. Friends must fail.

Gore Vidal

I have always felt that life was simply a series of personal humiliations relieved, occasionally, by the humiliations of others.

Lorrie Moore

Happiness is an agreeable sensation arising from contemplating the misery of another.

Ambrose Bierce

Insensitivity.

Tennessee Williams’s definition of happiness

We become moral when we are unhappy.

Marcel Proust

It is foolish to tear one’s hair in grief, as though sorrow would be made less by baldness.

Cicero

It is pretty hard to tell what does bring happiness: poverty and wealth have both failed.

Frank McKinney Hubbard

Have I not reason to hate and to despise myself? Indeed I do; and chiefly for not having hated and despised the world enough.

William Hazlitt, On the Pleasure of Hating

There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn.

Albert Camus

Trying is the first step towards failure.

Homer Simpson

I have no patience whatever with these Gorilla damnifications of humanity.

Thomas Carlyle on Charles Darwin

Only two things are infinite, the universe and human stupidity, and I’m not sure about the former.

Albert Einstein

Think of how stupid the average person is, and realise half of them are stupider than that.

George Carlin

Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach. Those who can’t teach, teach gym.

Woody Allen

There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labour of thinking.

Sir Joshua Reynolds

The human mind treats a new idea the same way the body treats a strange protein: it rejects it.

Anatomist P.B. Medawar

The majority of minds are no more to be controlled by strong reason than plumb-pudding is to be grasped by sharp pincers.

George Eliot

Those who know their minds do not necessarily know their hearts.

François de la Rochefoucauld

Many people would sooner die than think. In fact, they do.

Bertrand Russell

Life is tough, but it’s tougher when you’re stupid.

John Wayne

Real stupidity beats artificial intelligence every time.

Terry Pratchett

To err is human but to really foul up, you need

computers.

Anonymous

Computers are useless. They only give you answers.

Picasso

If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar that stretches on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well-wadded with stupidity.

George Eliot, Middlemarch

Drinking when we are not thirsty and making love all year round, madam; that is all there is to distinguish us from other animals.

Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, Le Mariage de Figaro

The human race, to which so many of my readers belong.

G.K. Chesterton

He grew up from manhood into boyhood.

Ronald Knox on G.K. Chesterton

It must be a sign of our times that I was asked to observe two minutes’ silence at my local library.

Doug Meredith on Remembrance Day

Society is now one polish’d horde,

Form’d of two mighty tribes, the Bores and Bored.

Lord Byron, Don Juan, XIII

All charming people have something to conceal, usually their total dependence on the appreciation of others.

Cyril Connolly

Style, like sheer silk, too often hides eczema.

Albert Camus, The Fall

I sometimes think that God, in creating man, somewhat overestimated his ability.

Oscar Wilde

A certain type of man is only stirred to the heights of passion by administrative inconvenience.

Anthony Powell

No one ever lacks a good reason for suicide.

Cesare Pavese, who committed suicide in 1950

Millions long for immortality who do not know what to do with themselves on a rainy Sunday afternoon.

Susan Ertz

No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

Extreme hopes are born of extreme misery.

Bertrand Russell

No lesson seems to be so deeply inculcated by the experience of life as that you never should trust experts. If you believe the doctors, nothing is wholesome: if you believe the theologians, nothing is innocent: if you believe the soldiers, nothing is safe. They all require to have their strong wine diluted by a very large admixture of insipid common sense.

Scorn

Scorn